AI Before AI Vanishes

In next to no time the Internet, smartphones, and social media utterly transformed life, to a point where people can’t imagine a world without them any more than they can imagine a world without tap water. The same thing will happen with AI. Let’s take a minute to admire its strangest attribute, before it’s too late to notice.

Artificial intelligence is here, a wonder about to disappear into the world. This kind of thing has happened many times in the history of technology. People marveled when night became day, but now no one thinks “electric light arrived,” nor do they take time from their smartphones to think “computers are here, everywhere.” We assume these things as part of our waking reality, and we are more likely to be sweating over the prospect of a blackout or a dead battery than we are thinking about how it changed us when the technologies first showed up.

AI is curious to us now, and the subject of much debate, but experience shows it won’t be as socially visible when it pervades our physical and digital lives to a point of invisibility. We now debate its intrusion in sectors, like AI in photos, AI in education, or AI in cars and at drive-in windows. It’s harder to contemplate AI in the weft of our being. Perhaps because then we’ll be partly made of it, and thus it will be harder to see it clearly.

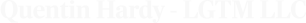

That isn’t as weird as it may seem. Technology has changed consciousness many times before, affecting our sense of ourselves and thus the world, and thereby compelling us to seek new things from ourselves and others. The mid-15th Century printing press increased the speed of production and the abundance of books. It made possible a new European relationship to God, the Protestant Reformation, through Martin Luther’s skillful use of pamphlets and broadsides against the slower-moving Vatican. It meant new and cheaper ways to store information that it made irrelevant the virtue of deep memorization. The telescope and its reversal, the microscope, showed unseen worlds and spurred the idea of hierarchical order in scientific understanding. Matthew Brady’s field camera delivered to millions the chaos and horror of Civil War battlefields, and the heroism of ordinary soldiers, as no painting could. Photography eased immigration, since people didn’t disappear from each other if they could carry pictures of their loved ones or send home images of their new selves. In the conflict of fascism and democracy, Adolph Hitler broadcast himself shouting in roaring stadiums, while Franklin Roosevelt spoke intimately in his weekly fireside chats. Film stands in for consciousness in the first pages of “The Great Gatsby,” and contemporary accounts of World War II battles speak of them as being “like a movie.” No need to dwell on the effects on individual consciousness and changing political dynamics with the Web and social media. “Changing ourselves with technology” may be a hallmark of the species.

If technology changes consciousness, it follows that much of our reality is a construct, mediated by the tools we use. This postmodern conclusion doesn’t bother anyone, since we assume that underlying realities like love and desire, ambition and fear, joy and the need for connection, don’t change. John Caulkin was right back in 1967: “We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us,” but no one has worried about it. We mostly assume a larger kind of continuity too. AI may challenge this, since it is going deep into our every action. It may already steer some of them.

Tech history also shows frequent anxiety about change. My personal favorite is the late-15th Century abbot who worried in a (machine printed) volume that his monks would fall to Satan now that copying out manuscripts was obsolete. Nathaniel Hawthorne complained that telegraphy had made the world a giant brain. Evelyn Waugh bemoaned the way Oxford students got drunk and listened to the gramophone, instead of getting drunk and reciting poetry by the yard, like his generation. My father wondered why I spent so much time bewitched by the idiot box. Virginia Heffernan recently noted that Jonathan Haidt worries about the “epidemic of mental illness” from social media in his recent book, which he offers as an e-book and promotes on Instagram, YouTube, and Tik Tok. Plus ça change. Samuel Morse’s first telegraph message was a quote of the Book of Numbers’ (“What hath God wrought”) that in the Bible ends with an exclamation point, signifying might. We read it now with the question mark of indeterminacy.

Some fears of change are justified, and some are simply plays to fear. When I was a tech journalist, a veteran reporter told me that “the robot only gets on the front page if by the third paragraph it’s killing someone or taking their job.” He was joking, I’m sure, though he had a good average in getting his stories prime placement. More seriously, Haidt may well be right about the effect of social media on teenagers. There’s certainly the phenomenon of distracted driving from phones (which may be solved by putting people in robocars – a classic case of solving tech with more tech). There are deep fakes and misinformation. Raising concerns about these things may actually lead to regulation, or even curb their use through social pressure. Which is to say, they will disappear into the world in more intentional and specific ways. We won’t eliminate them, these things that didn’t exist 20, or even five, years ago. That has happened before.

The process is familiar, yet there is something uniquely odd about the advent of AI. It comes soon after the self-changing technologies like the Internet and mobility, which we still haven’t fully processed. And it’s bigger than those. My previous employer Sundar Pichai has spoken of AI as being “more profound than fire or electricity.” Jack Clark, a cofounder of the AI company Anthropic, prefers to call it “functionally, an alien species.” Those are only clues to the strangest thing about AI as it disappears into our world. It’s not simply that we know it’s powerful, or that we now have so many examples of tech changing consciousness, which means we’re on the cusp of some new, unknowable break in consciousness, a novel explosion, a future shock to end them all. It’s impossible to say how something new and novel will turn out, except that it’s likely that the mental model we now inhabit will be utterly unrecognizable to our grandchildren.

That is not in itself the strangest thing, nor is it that many of the people working hardest to bring about AI believe it could destroy humanity. Though that is close; the strangest thing is the way neither the destruction of our world or the erasure of our current consciousness, one possible and the other nearly certain, seems to slow us down for a day.

We are making a future that we know will have at best a pallid understanding of the reality we now inhabit, little better than we can experience the human mind before electricity, photographs, widespread print, and all the rest. And that barely registers when we talk about AI. Such is the power of the prospect of a new technology, and the transcendence it may bring.