A 700 Year Old UX

Handling old manuscripts feels like time travel. What we can learn from an object created before the printing press standardized most design, when people read in entirely different ways.

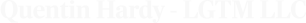

Sometime around the year 1300 a group of scholars, copyists, and binders made this book, now stored in an archive in Milan’s Sforza palace. The design is called a girdle book, constructed to be hung from a belt or sash from the leather loop attached to the binding, upside down and backwards, so that the book could be lifted, the vellum leaves unfolded, and the words read during breaks in a day. Pockets were coming on the scene around then, but something like this would have been too big and heavy for them. Plus, maybe bragging rights.

This book was most likely made for a monk, since the cover is unadorned and it has no illustrations. The text is based on St. Bonaventure’s “The Mind’s Road To God,” a 13th Century Franciscan’s exercises designed to aid the reader find God amid this sensory world (about the same time this book was made, Dante put St. Bonaventure in his Paradiso.) Girdle books and books on chains were also popular with aristocrats for about 300 years, though their content was more likely about observing the correct prayer rituals during a day, and unlike this workhorse had pleasing illustrations. They fell out of fashion once printed books became widespread and cheap.

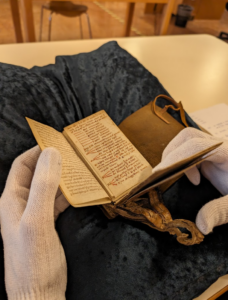

As with most manuscripts, the text has few visible errors If the copyist did goof, the bad letter was scratched out and written over. Many people may have worked on the writing over the many months put into creating this, though the hand is similar throughout. Judging from the signs of wear on the cover and folds it was read many times, mostly by several people seeking spiritual elevation. Yet it is remarkably intact.

Like many artifacts, it’s both a curiosity and a challenge. It now looks kind of strange, since we’re got a different standard of what a book should look like, how it should be read, and how to store it. Then as now, though, no one knew the future; they couldn’t imagine identical books cranked out by the thousand per hour, let alone today’s infinitely mutable books, in print or spoken word format. This was a singular object, made to be studied repeatedly over months and years.

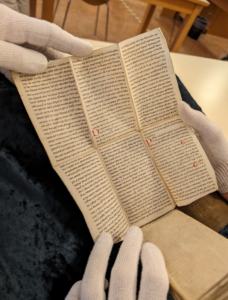

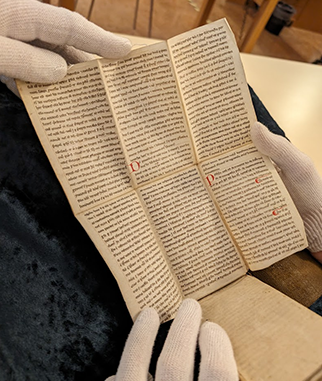

Vellum is a fine animal membrane, usually calfskin, that is painstakingly treated to create a reading material that was supple and easy on the eye. The ink, usually made by the scribe, is a mixture of a wasp gall on an oak tree, iron sulfate, and the gum of a North African acacia tree brought to Europe by Arab traders. Some elements of Bonaventure’s text deals in threefold meanings, and you can see where the commentator and copyist have labored to indicate this by branching the text.

For all that’s strange, this is a remarkably successful piece of technology. It served its purpose for generations, and after seven centuries and multiple iterations of what a book is, we can quickly understand how to use it, why it’s appropriate to its task, and the pleasure its use affords. In other words, a user experience with a durability that today only exists in dreams.

* All photos above © LGTM LLC no unauthorized reproduction or distribution